Through chronicling the evolution of her modest garden in Brighton, Bradbury makes the often-overwhelming concepts of climate change and biodiversity loss tangible to the reader. Through witnessing the struggles and triumphs of her garden – the lows of losing dragonflies to a spring drought and the joy of the first fledgling robins – we get to know Kate’s garden, and its heroes, personally.

With different narratives, the garden’s inhabitants – such as Doughnut the chunky rescue hedgehog and the amorous amphibians in amplexus (a mating embrace whereby frogs hold on to each other for hours) – each showcase their unique role in the intricate balance of the garden ecosystem. The herring gulls, for instance, become symbols of resilience, navigating an urban landscape fraught with hazards. The pollinating insects and their dependence on specific plants highlight the need to feed the bees.

By spotlighting these animals, Bradbury inspires a deeper appreciation for our gardens’ often-overlooked creatures.

Bradbury’s personal approach to storytelling can act as a catalyst for change, inspiring readers to reconsider what they do with their own green space, no matter how tiny. My research has shown that creating a mini-meadow of just two square metres can substantially and rapidly increase the abundance and diversity of wild bees and other pollinators. Others have demonstrated the importance of wildlife-friendly structures such as ponds and nest boxes for a variety of urban animals. Gardening for wildlife benefits us too, increasing our connection to nature and the health and wellbeing benefits that can bring.

Hope and action

In June, one of the biggest-ever marches for nature took place in London, with thousands of people joining over 350 environmental groups calling for the government to “Restore Nature Now”. Kate was there and so was I. The day was a much-needed reminder that many people care about our wildlife and are willing to take action to protect it.

Both Kate Bradbury and Elizabeth Nicholls attended the recent Restore Nature Now march in London. Beth Nicholls., CC BY-ND

Bradbury’s book is imbued with hope too — active, determined hope that channels her worry into constructive action, such as launching a hedgehog group to encourage her local community to provide a habitat for these declining animals. As with her neighbours, Bradbury urges us to become stewards of our local green spaces.

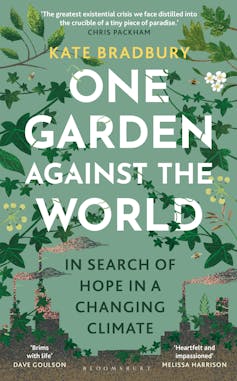

Bloomsbury, CC BY-ND

Small actions

If you’re feeling overwhelmed at the prospect of transforming your garden into a wildlife haven then fear not. Kate tells us where to start, from tiny actions such as leaving water out for animals, to the more involved and time-consuming projects, such as planting a hedge.

Her suggestions for alternative pest control methods, such as attracting slug-eating sloworms encourage a shift away from environmentally damaging pesticides, aligning with a broader trend in nature writing that began with Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, first published in 1962.

This seminal work brought awareness to the dangers of toxic chemicals, while contemporary writers like Bradbury focus not only on the threats to nature but on steps individuals can take to protect it. Dig a pond, make a hoverfly lagoon, create a log pile – these things need not take up too much space, nor cost much money, but they will make a big difference to wildlife, and Kate’s garden is proof of that.

One Garden Against the World is a call to action for anyone interested in gardening, conservation or climate change.

Bradbury’s engaging narrative and actionable advice make this book an essential read for urban dwellers looking to make a positive impact. Her work is especially inspiring for those who might feel powerless in the face of global challenges, demonstrating that significant change can start right in our own gardens or local green spaces. Through her small garden, Bradbury shows that each of us has the power to make a difference, one garden at a time.![]()

Elizabeth Nicholls, Research Fellow in Ecology, University of Sussex

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.