I recently went the Australian Circular Fashion Conference in Sydney and during a breakout session, a surf brand brought up the issue of microfiber pollution and how to move forward.

Considering the topic of microfibers has been talked about for a few years, it felt frustrating to go round in circles with not one person having a tangible solution.

Mainstream media has been documenting the topic for years, from The Guardian to The New York Times (The Green Hub also published an article ‘Plastic Pollution…’ last year).

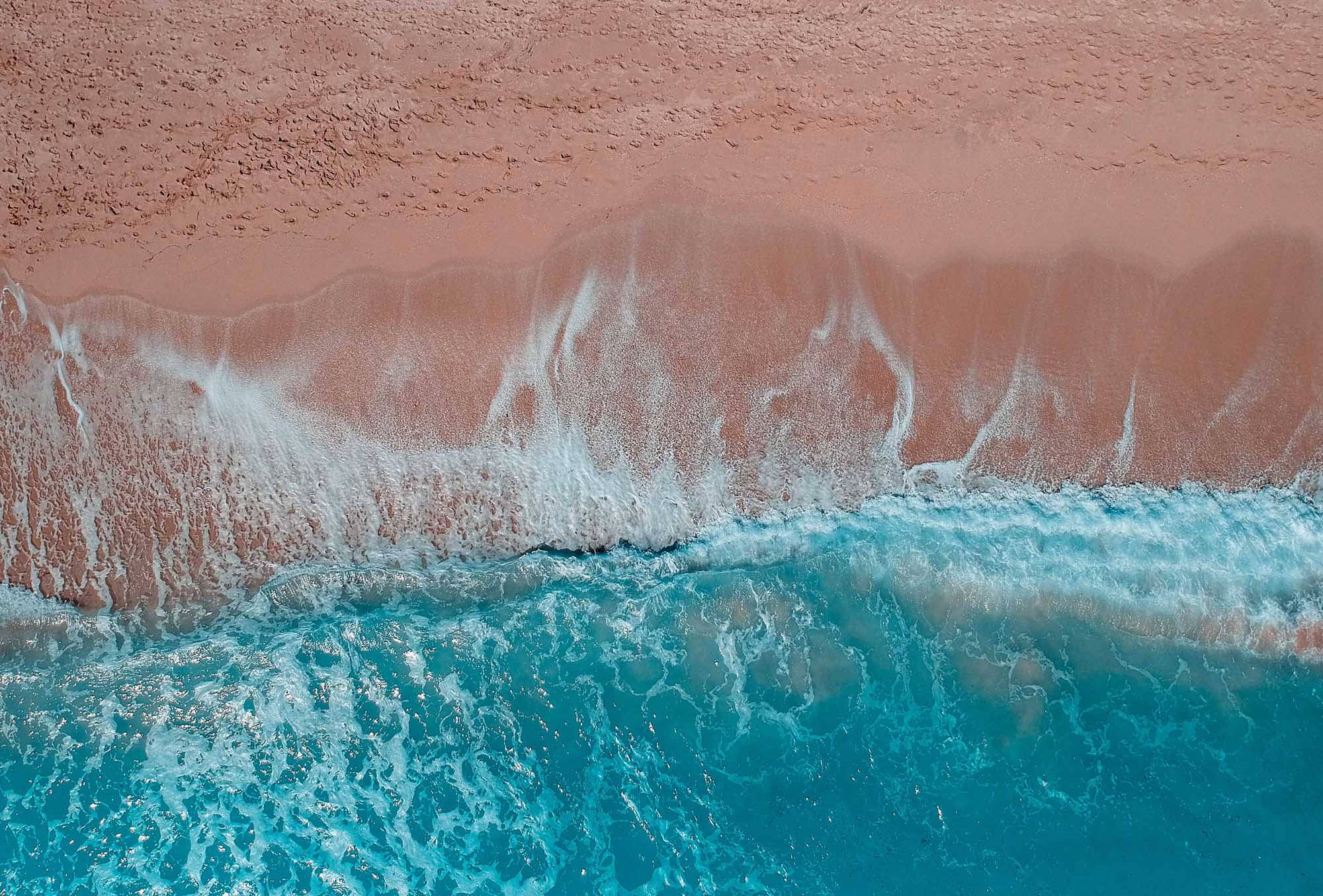

"They’re in your clothes, working their way through the washing machine, travelling through drains and out sewage outfalls. Then before you know it, they accumulate in the ocean at incomprehensible levels!" Mission Blue, ‘Microplastics causing macro-danger’, 2015

There seems to be consistent articles and videos circulating social media, highlighting the shocking fact that tiny fibers from clothing are seeping into the ocean from washing machines, polluting the ocean and ending up in the food chain.

How did we get here?

The issue of plastic pollution has been known for a while; leading to the recent phasing out of plastic items worldwide, for example selective supermarkets in Australia banning plastic bags. The connection between micro-plastic in the ocean and clothing was actually found in 2011.

Sydney based ecotoxicologist Dr Mark Browne and his team published a study in 2011 on the findings, ‘Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Worldwide: Sources and Sinks’. The study found that the dominant source of plastic in the ocean was from microfibers, from textiles. Mark went a step further showing that by washing various textiles; over 2,000 fibers were released per wash into the environment.

Considering the fashion industry isn’t exactly the cleanest and society’s demand for cheap, synthetic fast fashion has exponentially expanded, microfibers are not going away without action. Dr Mark Browne has worked relentlessly over his career to highlight the disastrous effect of microplastic, continuing to do so here in Australia.

A quick update

The real issue with microfiber pollution is that there is still a lack of understanding and knowledge.

This is mainly due to the fact that it’s not possible to see the pollution clearly. Finding a plastic straw in the ocean is gross and the cause is clear – straws. Drink with your mouth or a metal straw. Microfibers from clothing are near invisible to the eye and therefore don’t have an obvious impact on the ocean and therefore less of a demand for a solution. This makes it incredibly difficult to tell brands and consumers about the issue and how to solve it.

From my research, there has been no significant breakthrough towards solving the problem. This is clearly because it’s a fucking mess to solve and the solution is not a simple one.

Synthetic clothing may cause microfiber pollution, but natural cotton for example consumes excess amounts of water and toxic chemicals. It’s a delicate balance to finding a well-researched solution. Thankfully, there are organisations starting to invest in finding long-term solutions and hopefully there will be a consumer shift after education, to more natural and well-made clothing.

Image: Patagonia

Short term

Everyone’s favourite outdoor brand Patagonia is the most well known brand to be working on the issue.

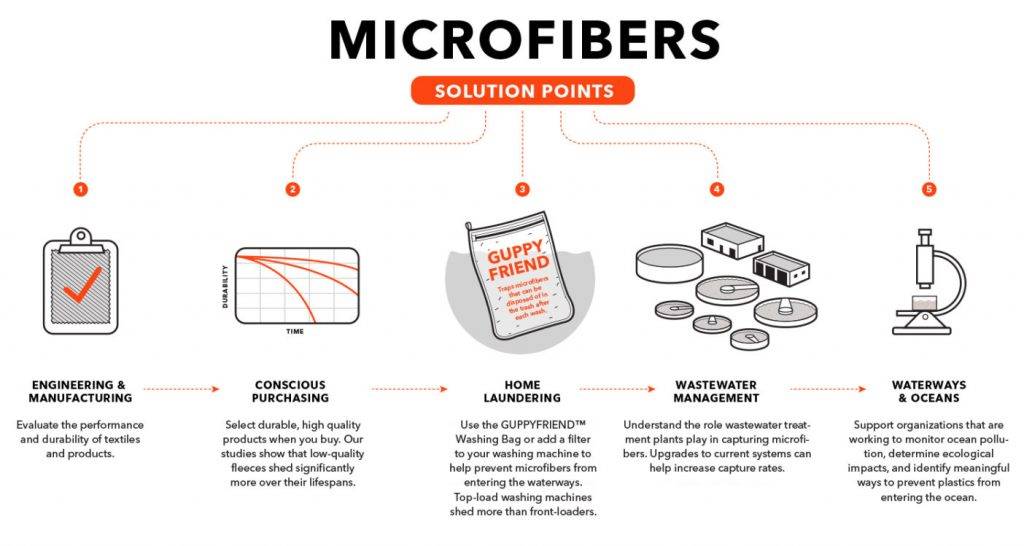

They have invested in microfiber research and published a comprehensive update in 2016, in which other brands can learn from. They have longer-term goals to better understand the impacts and improving garment construction, however for now their recommendations are focused on consumer behaviour. The below advice has been taken from ‘The Cleanest Line’ study from Patagonia, published in 2016.

- Buy only what you need

- Take care of what you have

- Buy good quality clothing that will shed less

- Wash less often

- Wash with a front-load washer if possible

There are also inventions such as ‘The Guppy Friend’, ‘Cora Ball’ and washing machine filters that I have previously discussed. These are however short-term solutions, to a complicated and serious issue that needs longer-term solutions.

![]()

Long term

When we convened a group of scientists, academics and public advocates at our headquarters in Ventura to discuss microplastics pollution with our leadership team, a clear consensus emerged at the end of a long, fascinating day: There’s a lot we don’t know.

Patagonia Press Release ‘The Cleanest Line’, Feb 2017

The most common feedback from the microfiber and textile experts that I’ve asked over the past year about microfibers is that there’s a need for more research and innovation. This is a two-fold requirement, as research requires funding and interest, which comes from the government and the industry.

Education is also another key area of focus, for both designers and consumers. The Swedish environmental research institute, Mistra, has been focusing on research at the design stage to combat microfiber pollution. They published a study ‘Microplastics shedding from polyester fabrics’ last year, finding the below.

- Virgin polyester sheds more than recycled polyester in a jersey & a microfleece

- If microparticles are removed at the production stage, microfibers are greatly reduced

- Ultrasonic cutting shed less considerably less fibers than scissor cutting

The conclusion of the study was that there is very little research on the topic, which is required to move the problem forward.

‘…Very little is known about how the fabric construction is linked to the shedding of microplastics. In addition, the few studies made give non-consistent results’.

Dr Mark Browne set up Benign By Design, which also works on educating companies on which textiles to use by providing a trade-off analysis system. There are also other organisations working on the issue including: Greenpeace, IUCN & The Plastic Soup Foundation.

Consumers also need to be accurately educated on the impacts their clothing has by brands giving transparent information. If consumers were to also buy less and invest in well-made and natural material clothing, there would be considerably less microfibers in the ocean.

The consumer has the power – educate others, take short-term action & pressure brands and the government to do something!